Letter from the Director

Ozlem Goker-Alpan, MD

We are presenting our 2023 newsletter, which is a synopsis of the latest news of the research conducted at LDRTC. We are looking ahead to our teamwork to bring new understanding to the different aspects of lysosomal diseases and unravel new treatment options for patients with rare disorders.

Over 300 million people and families around the world are directly affected by a rare disease. The month of February is special for the rare disease community. This is when we raise awareness and celebrate the lives of those affected by these serious and not well-understood disorders. At LDRTC, our mission is to bring the rare disease patients reasons to be hopeful for the future.

LDRTC is a unique institution with a dedication to improving the lives of individuals with LSDs and other rare diseases by providing clinical services, access to a variety of clinical trials, and bench-to-bedside projects with clinically meaningful outcomes. We are able to spend days, if needed, with the patients and families to understand the root of the issues and offer help with a whole-listic approach. In today’s health care system, where the clinical services are compensated by the third party payors, care is limited to a maximum of 54 minutes (a level 5 clinical visit); this could be considered utopic. In 2023, the theme for Rare Disease Day was “equity,” with a proposed definition of social opportunity, non-discrimination in education and work, and equitable access to health, social care, diagnosis, and management for patients with rare disorders. Health equity for patients is only conceivable by outcomes consequential to early diagnosis and expert clinical management, a rarity even with any developed country standards. Disorders are expensive diseases that the payors try to run away from. Thus, the care of a patient with a rare disorder becomes a saga with many interruptions and fractured medical services. Not the physician but the insurance companys’ flow chart decides how the patient is managed and treated. We “experts” deal with the rabbit hole of continuous denials and appeals.

The gaps in healthcare for patients with lysosomal disorders are further augmented by the paucity of experts to train the medical community. Similarly, generating experts and mentors in the field is not only expensive but time-consuming. From the health care provider’s perspective, it requires self-sacrifice and altruism. For the younger trainees who are after work-family balance, the gravity of the diseases, the complexity of the care, and the lack of fair compensation make rare diseases not an attractable professional choice.

For more than two decades that I’ve been working with families and patients with lysosomal disorders, I’ve witnessed many struggles while they go through this long journey called life. I feel privileged to know these warriors, big and small, who are the personification of endurance and resilience. All of this makes it worth every minute that we spend with and for the patients, giving true meaning to our existence professionally. While the rare community continues with its fight for a better tomorrow, LDRTC will always be by its side!

Thank you.

Ambroxol and Lysosomal Storage Disorders

By Ozlem Goker-Alpan, MD

Inflammation plays an important role in the pathophysiology of lysosomal storage disorders. It has been shown that the genes regulating the inflammatory response, such as though macrophage activation, are shared with the ones that regulate the autophagy pathway (Greene, 2022). It has been postulated that chronic inflammatory response and proinflammatory cytokine production due to the stored substrate further drives the substrate production and results in disease progression. The opposite is true, when the inflammation and secondary cytokine production are inhibited pharmacologically in animal models, the mice were protected from the adverse effects of the substrate storage and survived (Pandey, 2017).

Lysosomal disorders are heterogeneous even among patients with the same disease, sharing similar genotypes. For example, in patients with Gaucher disease who are homozygous for L444(483)P variant, while the presentation is commonly of a young child with hepatosplenomegaly, low platelets and slowed saccades, the phenotypes may range from acute neuronopathic form to the lack of primary nervous system involvement. While a mutation in the glucocerebrosidase gene is required to cause Gaucher disease, other factors play an important role in the manifestation of the disease. Glucocerebrosidase is a lysosomal enzyme, synthesized on endoplasmic reticulum (ER)bound polyribosomes and translocated into the ER. Following N-linked glycosylation, it is transported to the Golgi apparatus, from where it is trafficked to the lysosomes. It has been shown that mutant glucocerebrosidase variants present with variable levels of ER retention and ER-associated degradation (ERAD) in the proteasomes. The degree of ER retention and proteasomal degradation is suggested to be one of the factors that determine the severity of Gaucher disease (Ron and Horowitz, 2005).

Pharmacological chaperones (PC) are small molecules that can help to refold the mutated protein to prevent ERAD and proteosomal degradation. While a PC could help with ERAD, the main challenge is not only to enhance the enzymatic activity, but also further improve the downstream cellular processes, such as ALP pathway, mitophagy and mitochondrial functions, all of which will have an effect on protein folding, and further stabilize the intracellular environment. Inflammatory process is the common downstream pathway for all the LSDs. It has been recently shown that ALP functions and macrophage activation are regulated by the shared genes of the autophagy pathway.

Ambroxol (ABX) has been used as an over-the-counter drug for more than three decades in various countries, including Western Europe and Japan, as a mucolytic agent. There are various forms of Ambroxol such as tablets, syrup, and caplets of varying strengths, including an intravenous solution (Kantar, 2020). Ambroxol is a secretolytic agent, and a Na+ channel blocker (Gupta, 2010). In addition to its indication in both adult and pediatric patients with acute and chronic bronchopulmonary disease associated with impaired or abnormal mucous secretion or transport, in newborns, Ambroxol is also used for the treatment of airway mucus-hypersecretion and hyaline membrane disease (Hasegawa, 2006). Ambroxol inhibits both sodium currents through TTX-S and TTX-R, (Weiser and Wilson, 2002). Ambroxol increases the Cl(-)-dependent secretion. Ambroxol is an anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory agent, and was shown to prevent inflammation through Th1 cytokines (Takeda, 2016) (Malerba, 2008).

Ambroxol is a mixed PC for GBA1, identified through screening using heat inactivation technique (Maegewa, 2009). Studies conducted in Japan and Korea using high dose Ambroxol in patients with neuropathic Gaucher disease showed that Ambroxol was safe and might help to arrest the progression of the neurological manifestations, as evidenced by enhanced residual GCcase activity observed in all patients. With high doses, there was decreased frequency of seizure activity and improved neurocognitive functions (Kim, 2020).

As ABX could fold GBA1 protein to a more functional state, we asked whether patients carrying GBA1 variants that are amenable to ABX chaperone activity present with phenotypes that vary for their given genotypes. In vitro response to Ambroxol was tested in PBMCs and/or fibroblasts and overall survival, and other morbidities were assessed in 12 children with genotypes predicting Gaucher disease type 2. In this cohort, the most common GBA variant was L444P(8/12). Ambroxol response was negative if GCase increased 20% or less and was associated with mortality by 24 months or ventilatory support, and positive if GCase activity was increased 100% or more, and a survival without tracheostomy beyond age 5 or mild delays and unassisted walking. This study shows that pharmacologic chaperones such as ABX could modify the Gaucher disease course, but also may aid in identification of attenuated forms through in vitro testing.

Cardiac Imaging in Patients With Fabry Disease

By Omar Abu Slayeh, MD

In FD, chronic inflammatory response is one of the downstream events associated with the disease progression. In the cardiac tissues, the infiltration of lymphocytes and macrophages suggest that inflammation plays a significant role in cardiac damage in FD cardiomyopathy. NF-κB and TNF signaling pathways (MCP-1, INF, TGF-β) play a subsequent role in inflammatory response and the progression to fibrosis. Activation of coronary angiogenesis (VEGF) further plays a role in cardiac vascularization and pathological hypertrophy.

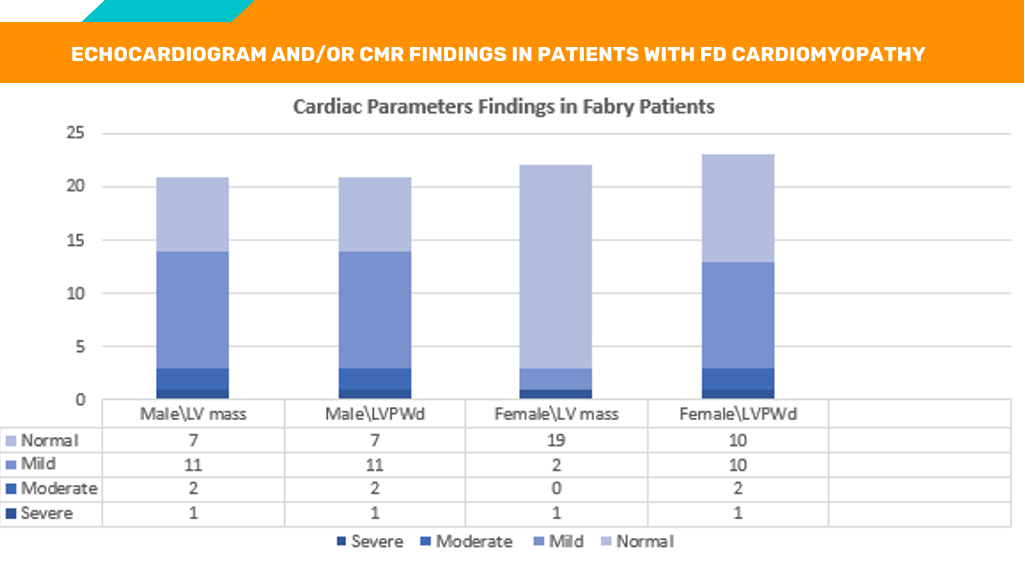

We studied 43 patients with Fabry disease and 20 healthy controls (10 males and 10 females with average age 48 ± 11 yrs). Clinical presentation, GLA activity and molecular analysis confirmed the diagnosis of FD. The subjects were further categorized into groups based on echocardiographic and cardiac MRI with late gadolinum enhancement (CMR/LGE) findings, left ventricular mass (LVM), and LVPWD measurements. The cohorts included: No cardiac involvement, or mild, moderate, and severe hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Below are the main observations from this study:

Outcomes of Enzyme Replacement Therapy in Infants and Young Children With Gaucher Disease

Nazish Khan

Gaucher disease (GD) is an inherited metabolic disorder that causes an accumulation of harmful lipids, particularly glucocerebroside, and affects various organs, including bone marrow, spleen, and liver. This accumulation is caused by the absence or deficiency of the enzyme β-glucocerebrosidase. There are three types of Gaucher disease, GD Type I-Non neuronopathic (most common), GD Type II-Infantile (often fatal), and GD Type III-neuronopathic. Type I is the most common among people of Ashkenazi Jewish descent. Gaucher Disease affects approximately 1 in every 20,000 live births.

Enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) may aid in preventing GD complications when administered early. Velaglucerase alfa (VPRIV) is approved as an ERT for GD; however, administration parameters in very young pediatric patients remain unknown. This is a phase 4, observational, retrospective/prospective, non-controlled, non-comparative, single-center, single-cohort study that has the objective to determine if ERT improves growth and other GD-related symptoms in children who are four years old or younger. Each eligible patient’s data is collected for at least 18 months and prospectively up to 36 months.

This study, which was initiated in January 2021, is currently enrolling, has eight patients enrolled, and will continue through 2025. One patient is five years old and has participated in the study for over 18 months. Most of the patients obtain their ERT via home infusions. The remaining patients visit their local clinics, hospitals, or LDRTC. All of the patients receive 60 to 80 units of ERT weekly or biweekly, and have shown an increase in growth, and improvement of GD-related signs and symptoms. There were no drug-related adverse events recorded. The data obtained from this study will help to assess the safety and effectiveness of ERT in young children, providing valuable treatment information for pediatric patients with Gaucher disease.

Goker-Alpan et al., 101 World Symposium 2022

Simultaneous Heart and Kidney Transplantation in a patient with Fabry Disease

Omar Abu Slayeh, MD

Comorbidities have an important impact on the decision about acceptance of patients for cardiac transplantation. Due to the rarity of Fabry disease, and the small percentage of patients who received heart transplantation, information on heart transplantation outcomes in Fabry disease is scarce.

We describe the case of a 59-year-old man with Fabry disease, who had chronic renal disease and systolic heart failure, who received a successful simultaneous heart and kidney transplantation. In the literature, renal transplant is described, and is offered to patients with Fabry disease who develop end stage renal disease. However, there is a very small percentage of patients who underwent heart transplantation. The patient was diagnosed with Fabry disease at the age of 27 and started on enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) since the diagnosis. The patient received his first kidney transplantation 6 years after the diagnosis of Fabry disease. Despite continued treatment with ERT, he had progressive worsening of FD cardiomyopathy with deterioration of the function of the transplanted kidney with an EGFR=17 (ref > or = 60mL/min/1.7 m2) and the ejection fraction (EF) was 30% on echocardiogram. A cardiac catheterization was performed, and showed no significant atherosclerosis in the left main coronary artery, left circumflex artery and right coronary artery. However, with moderate arm exercise during the catheterization, there was a significant decrease in LVEF. Due to the likely continued decline of the patient‘s renal and cardiac functions, he was placed on the transplant list. The patient received a successful simultaneous heart and kidney transplant when a compatible donor was found. After the transplant, the patient ejection fraction improved to 65%. The patient’s estimated glomerular filtration rate was 50 mL/min/1.73m2. Post operatively, the patient continued on enzyme replacement therapy.

Comorbidities have an important impact on the decision about the acceptance for cardiac transplantation. Renal function is a very important risk factor for mortality posttransplantation. Irreversible renal dysfunction with a GFR less than 40 ml/min can be considered as a relative contraindication for heart transplantation, as renal function is expected to further deteriorate as a result of the nephrotoxic immunosuppressive drugs. The incidence of chronic renal failure after a heart transplant could be up to 20% or more with poor prognostic outcomes. Many patients may end up on dialysis after the heart transplants (Jonge, 2008). Chronic renal insufficiency occurs commonly in patients with Fabry disease. In a case series from the National Institutes of Health, up to 50% of patients with Fabry disease developed chronic renal insufficiency, and 23% of patients developed end stage renal disease (ESRD). Treatment of patients with Fabry disease with ERT stabilizes and preserves kidney function. It is recommended to start treatment with ERT as early as the diagnosis of Fabry disease is made, as studies showed that ERT may be less effective when patients are in advanced stages of disease. It is reported that outcomes of kidney transplantation in patients with Fabry disease and the general population are comparable. Graft survival was similar in both populations.

Cardiac involvement in Fabry disease is common, and can manifest as coronary insufficiency, atrioventricular conduction disturbances, arrhythmias, valvular involvement, and cardiac hypertrophy. More research in the future is needed to elucidate the timing of the start of ERT in preventing cardiac dysfunction in asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic patients with Fabry disease. Due to the rarity of FD, and the small percentage of patients who had received heart transplantation, information on heart transplantation outcomes in this patient population is scarce. We found limited data on the long-term outcome of patients with Fabry disease who received a heart transplantation. One case report describes a patient who had good graft survival on follow up after 14 years. Like most, patients with Fabry disease may only be eligible for heart transplantation with end stage heart failure. However, other advanced therapies such, like left ventricular assist devices may not be employed due to the small left ventricular cavity diameter due to hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. This case demonstrates that patients with Fabry disease could be candidates for heart transplantation earlier than anticipated. Multi-organ transplantation even if there is accompanying end stage kidney disease could be successfully employed to save lives.

Desnick, R. J. et al. Fabry Disease, an Under-Recognized Multisystemic Disorder: Expert Recommendations for Diagnosis, Management, and Enzyme Replacement Therapy. https://annals.org (2003). Karras, A. et al.Combined heart and kidney transplantation in a patient with Fabry disease in the enzyme replacement therapy era. American Journal of Transplantation 8, 1345– 1348 (2008). Rajagopalan, N., Dennis, D. R. & OʼConnor, W. Successful Combined Heart and Kidney Transplantation in Patient With Fabryʼs Disease: A Case Report. Transplant Proc 51, 3171– 3173 (2019). Tran Ba, S. N. et al. Transplantation combinée cœur–rein au cours de la maladie de Fabry : suivi à long terme de deux patients. Revue de Medecine Interne 38, 137–142 (2017). Ersözlü, S. et al. Long-term Outcomes of Kidney Transplantation in Fabry Disease. Transplantation 102, 1924–1933 (2018). Breunig, F., Weidemann, F., Strotmann, J., Knoll, A. & Wanner, C. Clinical benefit of enzyme replacement therapy in Fabry disease. Kidney Int 69, 1216–1221 (2006). Waldek, S. & Feriozzi, S. Fabry nephropathy: A review - How can we optimize the management of Fabry nephropathy? BMC Nephrology vol. 15 Preprint at https:// doi.org/10.1186/1471-2369-15-72 (2014). Weidemann, F. et al. Long-term outcome of enzymereplacement therapy in advanced Fabry disease: Evidence for disease progression towards serious complications. J Intern Med 274, 331–341 (2013). Schiff mann, R. et al. Enzyme Replacement Therapy in Fabry Disease A Randomized Controlled Trial. https:// jamanetwork.com/. Warnock, D. G. et al. Renal outcomes of agalsidase beta treatment for Fabry disease: Role of proteinuria and timing of treatment initiation. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation 27, 1042–1049 (2012). Ojo A, Meier-Kriesche HU, Friedman G, Hanson J, Cibrik D, Leichtman A, et al. Excellent outcome of renal transplantation in patients with Fabryʼs disease. Transplantation. Inderbitzin, D., Avital, I., Largiadèr, F., Vogt, B. & Candinas, D. Kidney transplantation improves survival and is indicated in Fabryʼs disease. Transplant Proc 37, 4211–4214 (2005). Verocai, F., Clarke, J. T. & Iwanochko, R. M. Case report: Long term outcome post-heart transplantation in a woman with Fabryʼs disease. J Inherit Metab Dis 33 Suppl 3, S385-7 (2010). Seward, J. B. & Casaclang-Verzosa, G. Infiltrative Cardiovascular Diseases. Cardiomyopathies That Look Alike. Journal of the American College of Cardiology vol. 55 1769– 1779 Preprint at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2009.12.040 (2010). Jonge et al. 2008 Guidelines for heart transplantation. Neth Heart J

Patients With Gaucher Disease and Bone Pain Have Higher Rates of Bone Marrow Infiltration, Erlenmeyer Flask Deformity, Bone Fractures, and Cystic/Lytic Lesions

Margarita M. Ivanova, PhD

Patients with Gaucher disease (GD) have progressive bone involvement that clinically presents with debilitating bone pain, structural bone changes, bone marrow infiltration (BMI), Erlenmeyer flask (EM) deformity, and osteoporosis (Goker-Alpan, 2011).

Skeletal disorders are often accompanied by bone pain. In GD, the pain may continue to persist despite of therapy. The source of bone pain is still debated as nociceptive pain secondary to bone pathology, neuropathic or inflammatory origins. Bone disease in GD is a sum of progressive events that begin with irregular bone development as defects of vertebral remodeling and EM flask deformity (Kaplan et al., 2006; Pastores and Meere, 2005). Bone destruction (osteonecrosis, cystic/lytic lesions), accompanied by the reduction of bone mineral density leads to osteoporosis at an early age (Itzchaki et al., 2004; Ivanova et al., 2021; Ivanova et al., 2022). Brief Pain Inventory analysis from our cohort revealed that 45% of GD patients with normal mineral bone density, 45% with osteopenia, and 78% patients with osteoporosis report chronic pain. These data are commensurate with the literature that 27-63% of patients with GD have a history of pain (Goker-Alpan, 2011; Ivanova et al., 2021; Oliveri et al., 2020; Reed et al., 2018). While it has been considered that pain is a result of skeletal involvement in GD, but in the absence of bone disease, pain could occur without a clear explanation. Thus, the source of pain could be chronic inflammation, structural damage to the peripheral nervous system and/or infiltration of Gaucher cells in the bone marrow.

Infiltration of Gaucher cells in the bone marrow leads to thinning of the cortex, osteonecrosis, lytic lesions, and may cause pain (Hughes et al., 2019; Linari and Castaman, 2015). In addition, bone marrow infiltration induces abnormal bone remodeling. The modeling disorder of the distal femurs, Erlenmeyer flask deformity, is a common radiological finding in patients with Gaucher disease (Faden et al., 2009; Linari and Castaman, 2015; Wenstrup et al., 2002). Erlenmeyer flask deformity implies the involvement in childhood when the skeleton is developing. This deformity, resulting from defective bone modeling at the metadiaphyseal region, leads to straight uncarved di-metaphyseal borders and cortical thinning (Faden et al., 2009). However, cellular aspects of bone remodeling leading to EM-flask deformity are not fully understood. Several studies discuss that osteoclast impairment could be the cause (Adusumilli et al., 2021).

Wnt Signaling Pathway Inhibitor, Sclerostin, Is a Novel Biomarker of Bone Pathology in Gaucher Disease

Margarita M. Ivanova, PhD

Patients with Gaucher disease (GD) have progressive bone involvement that clinically presents with debilitating bone pain, structural bone changes, bone marrow infiltration (BMI), Erlenmeyer flask (EM) deformity, and osteoporosis (Goker-Alpan, 2011).

Skeletal disorders are often accompanied by bone pain. In GD, the pain may continue to persist despite of therapy. The source of bone pain is still debated as nociceptive pain secondary to bone pathology, neuropathic or inflammatory origins. Bone disease in GD is a sum of progressive events that begin with irregular bone development as defects of vertebral remodeling and EM flask deformity (Kaplan et al., 2006; Pastores and Meere, 2005). Bone destruction (osteonecrosis, cystic/lytic lesions), accompanied by the reduction of bone mineral density leads to osteoporosis at an early age (Itzchaki et al., 2004; Ivanova et al., 2021; Ivanova et al., 2022). Brief Pain Inventory analysis from our cohort revealed that 45% of GD patients with normal mineral bone density, 45% with osteopenia, and 78% patients with osteoporosis report chronic pain. These data are commensurate with the literature that 27-63% of patients with GD have a history of pain (Goker-Alpan, 2011; Ivanova et al., 2021; Oliveri et al., 2020; Reed et al., 2018). While it has been considered that pain is a result of skeletal involvement in GD, but in the absence of bone disease, pain could occur without a clear explanation. Thus, the source of pain could be chronic inflammation, structural damage to the peripheral nervous system and/or infiltration of Gaucher cells in the bone marrow.

Infiltration of Gaucher cells in the bone marrow leads to thinning of the cortex, osteonecrosis, lytic lesions, and may cause pain (Hughes et al., 2019; Linari and Castaman, 2015). In addition, bone marrow infiltration induces abnormal bone remodeling. The modeling disorder of the distal femurs, Erlenmeyer flask deformity, is a common radiological finding in patients with Gaucher disease (Faden et al., 2009; Linari and Castaman, 2015; Wenstrup et al., 2002). Erlenmeyer flask deformity implies the involvement in childhood when the skeleton is developing. This deformity, resulting from defective bone modeling at the metadiaphyseal region, leads to straight uncarved di-metaphyseal borders and cortical thinning (Faden et al., 2009). However, cellular aspects of bone remodeling leading to EM-flask deformity are not fully understood. Several studies discuss that osteoclast impairment could be the cause (Adusumilli et al., 2021).

Pharmacological inhibition of sclerostin by monoclonal antibodies as a potential therapy for osteoporosis

Margarita M. Ivanova, PhD

The most common therapies to treat bone pain are nonspecific such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and opiates. “Bone Pain Inventory'' analysis of our study showed that some of our patients used NSAIDS (such as ibuprofen), acetaminophen to treat pain, or, in instances of more severe pain, the management included opiates (Ivanova et al., 2022). While, NSAIDs can be effective to relieve bone pain, for extended usage there are hepatic, renal, or other vascular effects. Opiates for long-term use have the risk of dizziness, vertigo, and development of dependence. Moreover, these therapies do not treat the source of the actual disease; they only inhibit pain. The treatment of bone disease and chronic pain in patients with GD is complicated and often insufficient. Inhibition of osteoclast activity may be a solution to inhibit bone resorption and reduce bone pain. Bisphosphonates and Denosumab were initially developed to treat osteoporosis, but both therapies relieve pain in patients with bone cancer (Fabre et al., 2020). Pharmacological inhibition of sclerostin by monoclonal antibodies has been explored as a potential therapy for osteoporosis, fracture healing, and other bone disorders (Fabre et al., 2020; Rauner et al., 2021). Anti-sclerostin antibodies were shown to improve bone mineral density or fracture healing and may relieve skeletal pain (Fabre et al. 2020; Frost et al., 2016; Mitchell et al., 2018). Our study suggests that the Wnt signaling pathway plays an important role in GD-associated bone disease, and sclerostin could be a valuable biomarker to monitor patients with GD. The pharmacological inhibition of sclerostin by monoclonal antibodies as a potential therapy for osteoporosis need to be further elucidated in GD.

References:

Adusumilli, G., Kaggie, J.D., D'Amore, S., Cox, T.M., Deegan, P., MacKay, J.W., McDonald, S., and Consortium, G. (2021). Improving the quantitative classification of Erlenmeyer flask deformities. Skeletal Radiol 50, 361-369. 10.1007/ s00256-020-03561-2. Coulson, J., Bagley, L., Barnouin, Y., Bradburn, S., Butler-Browne, G., Gapeyeva, H., Hogrel, J.Y., Maden-Wilkinson, T., Maier, A.B., Meskers, C., et al. (2017). Circulating levels of dickkopf-1, osteoprotegerin and sclerostin are higher in old compared with young men and women and positively associated with whole-body bone mineral density in older adults. Osteoporos Int 28, 26832689. 10.1007/s00198-017-4104-2. Devigili, G., De Filippo, M., Ciana, G., Dardis, A., Lettieri, C., Rinaldo, S., Macor, D., Moro, A., Eleopra, R., and Bembi, B. (2017). Chronic pain in Gaucher disease: skeletal or neuropathic origin? Orphanet J Rare Dis 12, 148. 10.1186/s13023017-0700-7. Fabre, S., Funck-Brentano, T., and Cohen-Solal, M. (2020). Anti-Sclerostin Antibodies in Osteoporosis and Other Bone Diseases. J Clin Med 9. 10.3390/ jcm9113439. Faden, M.A., Krakow, D., Ezgu, F., Rimoin, D.L., and Lachman, R.S. (2009). The Erlenmeyer flask bone deformity in the skeletal dysplasias. Am J Med Genet A 149A, 1334-1345. 10.1002/ajmg.a.32253. Frost, C.O., Hansen, R.R., and Heegaard, A.M. (2016). Bone pain: current and future treatments. Curr Opin Pharmacol 28, 31-37. 10.1016/j.coph.2016.02.007. Gerosa, L., and Lombardi, G. (2021). Bone-to-Brain: A Round Trip in the Adaptation to Mechanical Stimuli. Front Physiol 12, 623893. 10.3389/ fphys.2021.623893. Goker-Alpan, O. (2011). Therapeutic approaches to bone pathology in Gaucher disease: past, present and future. Mol Genet Metab 104, 438-447. 10.1016/j.ymgme.2011.08.004. Holdsworth, G., Roberts, S.J., and Ke, H.Z. (2019). Novel actions of sclerostin on bone. J Mol Endocrinol 62, R167-R185. 10.1530/JME-18-0176. Hughes, D., Mikosch, P., Belmatoug, N., Carubbi, F., Cox, T., Goker-Alpan, O., Kindmark, A., Mistry, P., Poll, L., Weinreb, N., and Deegan, P. (2019). Gaucher Disease in Bone: From Pathophysiology to Practice. J Bone Miner Res 34, 996-1013. 10.1002/jbmr.3734. Itzchaki, M., Lebel, E., Dweck, A., Patlas, M., Hadas-Halpern, I., Zimran, A., and Elstein, D. (2004). Orthopedic considerations in Gaucher disease since the advent of enzyme replacement therapy. Acta Orthop Scand 75, 641-653. 10.1080/00016470410004003. Ivanova, M., Dao, J., Noll, L., Fikry, J., and Goker-Alpan, O. (2021). TRAP5b and RANKL/OPG Predict Bone Pathology in Patients with Gaucher Disease. J Clin Med 10. 10.3390/jcm10102217. Ivanova, M.M., Dao, J., Kasaci, N., Friedman, A., Noll, L., and Goker-Alpan, O. (2022). Wnt signaling pathway inhibitors, sclerostin and DKK-1, correlate with pain and bone pathology in patients with Gaucher disease. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 13, 1029130. 10.3389/fendo.2022.1029130. Kaplan, P., Andersson, H.C., Kacena, K.A., and Yee, J.D. (2006). The clinical and demographic characteristics of nonneuronopathic Gaucher disease in 887 children at diagnosis. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 160, 603-608. 10.1001/ archpedi.160.6.603. Kitaura, H., Marahleh, A., Ohori, F., Noguchi, T., Shen, W.R., Qi, J., Nara, Y., Pramusita, A., Kinjo, R., and Mizoguchi, I. (2020). Osteocyte-Related Cytokines Regulate Osteoclast Formation and Bone Resorption. Int J Mol Sci 21. 10.3390/ijms21145169. Linari, S., and Castaman, G. (2015). Clinical manifestations and management of Gaucher disease. Clin Cases Miner Bone Metab 12, 157-164. 10.11138/ ccmbm/2015.12.2.157. Mitchell, S.A.T., Majuta, L.A., and Mantyh, P.W. (2018). New Insights in Understanding and Treating Bone Fracture Pain. Curr Osteoporos Rep 16, 325-332. 10.1007/s11914-018-0446-8. Oliveri, B., Gonzalez, D.C., Rozenfeld, P., Ferrari, E., Gutierrez, G., and Grupo de estudio Bone Involvement Gaucher, D. (2020). Early diagnosis of Gaucher disease based on bone symptoms. Medicina (B Aires) 80, 487-494. Pastores, G.M., and Meere, P.A. (2005). Musculoskeletal complications associated with lysosomal storage disorders: Gaucher disease and Hurler-Scheie syndrome (mucopolysaccharidosis type I). Curr Opin Rheumatol 17, 70-78. 10.1097/01.bor.0000147283.40529.13. Rauner, M., Taipaleenmaki, H., Tsourdi, E., and Winter, E.M. (2021). Osteoporosis Treatment with Anti-Sclerostin Antibodies-Mechanisms of Action and Clinical Application. J Clin Med 10. 10.3390/jcm10040787. Reed, M.C., Bauernfreund, Y., Cunningham, N., Beaton, B., Mehta, A.B., and Hughes, D.A. (2018). Generation of osteoclasts from type 1 Gaucher patients and correlation with clinical and genetic features of disease. Gene 678, 196206. 10.1016/j.gene.2018.08.045. Sapir-Koren, R., and Livshits, G. (2014). Osteocyte control of bone remodeling: is sclerostin a key molecular coordinator of the balanced bone resorption-formation cycles? Osteoporos Int 25, 2685-2700. 10.1007/s00198-014-2808-0. Tu, X., Rhee, Y., Condon, K.W., Bivi, N., Allen, M.R., Dwyer, D., Stolina, M., Turner, C.H., Robling, A.G., Plotkin, L.I., and Bellido, T. (2012). Sost downregulation and local Wnt signaling are required for the osteogenic response to mechanical loading. Bone 50, 209-217. 10.1016/j.bone.2011.10.025. Wenstrup, R.J., Roca-Espiau, M., Weinreb, N.J., and Bembi, B. (2002). Skeletal aspects of Gaucher disease: a review. Br J Radiol 75 Suppl 1, A2-12. 10.1259/ bjr.75.suppl_1.750002. Xu, Y., Gao, C., He, J., Gu, W., Yi, C., Chen, B., Wang, Q., Tang, F., Xu, J., Yue, H., and Zhang, Z. (2020). Sclerostin and Its Associations With Bone Metabolism Markers and Sex Hormones in Healthy Community-Dwelling Elderly Individuals and Adolescents. Front Cell Dev Biol 8, 57. 10.3389/fcell.2020.00057.

LDRTC and CheckRareCE co-hosts Quarterly CME Series

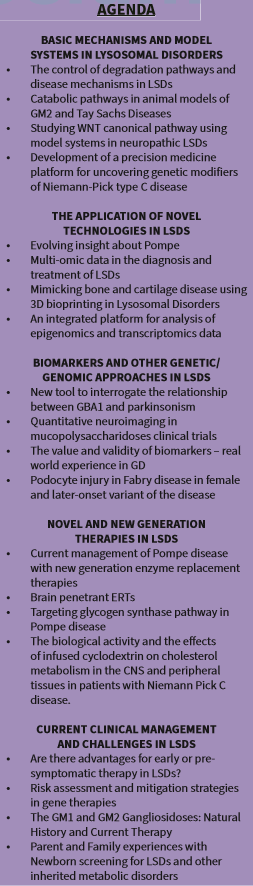

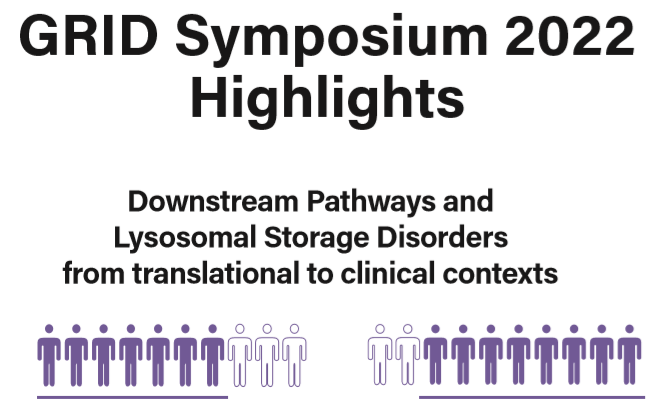

LDRTC hosted the 2022 Genetic, Rare & Immune Disorders Symposium (GRIDS) on November 20-21 in Fairfax, Virginia. This year’s event focused on the “Downstream Pathways and Lysosomal Storage Disorders from translational to clinical contexts”.

The symposium featured in-person and virtual presentations from researchers, physicians, and patient advocates from Brazil, Chile, Israel, Turkey, and the United States. During the first day of the event, experts in the field presented about basic mechanisms and model systems in Lysosomal disorders, the application of novel technologies, biomarkers and other genetic/genomic approaches in LSDs. On the second day, they addressed novel and new generation therapies in LSDs and current clinical management and challenges in LSDs.

Ozlem Goker-Alpan, MD, Founder/CMO of LDRTC, opened the symposium by highlighting the importance of this event and the reason behind the limited number of speakers. “It is a pleasure to host this annual event dedicated to the LSDs community. I’ve never intended for GRIDS to be a big symposium because I want this event to be a personal platform for experts in the field to exchange knowledge and showcase their latest findings that will eventually benefit our dearest LSDs community.”

GRIDS 2022 ended with the Expert LSD clinic, where world-renowned physicians advised a select group of patients on their challenging disorders.

The 8th edition of the summit was the first in-person GRID Symposium since 2019, when the pandemic hit. Subscribers were also able to attend the event from home. If you are interested in reviewing the 2022 GRIDS, with CME lectures, please visit http://www.gridssymposium.org